|

|

John Anderson Graham of Kalimpong was a unique human being who chose early in his life, the road less traveled. Born on 8th September 1861 in a small town, De Beauvoir in West Hackney District,John was the second son of David Graham, a Customs Officer by occupation and Bridget Nolan, a homemaker of Irish descent. The Graham family was a closely-knit family and deeply religious.

After David Graham’s retirement in 1862, the family moved to live on their farm “Glenboig”. It was here that John developed a keen interest in agriculture and farming, which was to stand him in good stead later. David Graham passed away in 1867. John attended the local parish school and imbibed the liberal and democratic values of the Scottish educational system. However, at the age of thirteen, he was withdrawn from school and sent to work in order to contribute to the family’s income. Due to his aptitude for figures, it was decided that he should become a clerk where the main job was licking stamps and delivering messages. Anxious to add to his limited school education, John attended evening classes at ‘The Andersonian” where he took an unlikely combination of subjects that included stenography and astronomy. He enrolled in high school in Glasgow in 1875. The teachers of the high school were a group of academicians chosen not only for their academic qualifications but also for their broad outlook. They influenced John Graham to broaden his perspective and their love of tradition and fair play had a powerful influence on his thinking and approach to life.

John Anderson Graham of Kalimpong was a unique human being who chose early in his life, the road less traveled. Born on 8th September 1861 in a small town, De Beauvoir in West Hackney District,John was the second son of David Graham, a Customs Officer by occupation and Bridget Nolan, a homemaker of Irish descent. The Graham family was a closely-knit family and deeply religious.

After David Graham’s retirement in 1862, the family moved to live on their farm “Glenboig”. It was here that John developed a keen interest in agriculture and farming, which was to stand him in good stead later. David Graham passed away in 1867. John attended the local parish school and imbibed the liberal and democratic values of the Scottish educational system. However, at the age of thirteen, he was withdrawn from school and sent to work in order to contribute to the family’s income. Due to his aptitude for figures, it was decided that he should become a clerk where the main job was licking stamps and delivering messages. Anxious to add to his limited school education, John attended evening classes at ‘The Andersonian” where he took an unlikely combination of subjects that included stenography and astronomy. He enrolled in high school in Glasgow in 1875. The teachers of the high school were a group of academicians chosen not only for their academic qualifications but also for their broad outlook. They influenced John Graham to broaden his perspective and their love of tradition and fair play had a powerful influence on his thinking and approach to life.

|

|

|

|

Globally, the British Empire was expanding into every corner of the world. It strode the world like a colossus and Victorian Britain, apart from the financial benefits it reaped, felt it had a duty to free the “natives” from the superstitions and fears of the religions they had practiced for centuries. It was an exciting time for missionary committees and many ministers, doctors, teachers and nurses received the call to serve in far away places with strange sounding names. To John, a self-confessed romantic, the missionary field with its freedom of action, with the opportunity it provided to explore new environments, with its position in the vanguard of empire building, held enormous attraction. After much deliberation and debate, it was felt that the Kalimpong Division of the Darjeeling Mission in India needed extended missionary activity. On Sunday, 13th January 1889, one thousand young guildsman from all over Scotland, gathered in St. George’s Church, Edinburgh, to witness the ordination of the popular young Minister, John Anderson Graham, who was going out as a crusader in God’s name, and in their name, to battle the “forces of darkness” in the mystic sounding Himalayas. The very name of ‘Kalimpong’ sounded intriguing and exotic, and even a little frightening. However, John was not going alone on this mission to the unknown. Two days after his ordination, he married Katherine McConachie whom he had met because of their common interest in child welfare work in the city. |

| |

John Anderson and Katherine Graham set out for Kalimpong via Switzerland, Austria and Italy and finally landed at Calcutta on 21st March 1889. On the 5th and 6th of April, 1889, the Grahams made their way to Darjeeling via the sprawling townships of Jalpaiguri and Siliguri which lie below the foothills of the Himalayas. They began the climb through the luscious forests on ponies through the tea gardens till they reached Darjeeling where John fell in love with the mountains, never to tire of their beauty. Kalimpong was populated by three main tribes – the Lepchas, the Bhutias and the Nepalese. John was attracted to working with the Lepchas, the original inhabitants. John Anderson and Katherine Graham set out for Kalimpong via Switzerland, Austria and Italy and finally landed at Calcutta on 21st March 1889. On the 5th and 6th of April, 1889, the Grahams made their way to Darjeeling via the sprawling townships of Jalpaiguri and Siliguri which lie below the foothills of the Himalayas. They began the climb through the luscious forests on ponies through the tea gardens till they reached Darjeeling where John fell in love with the mountains, never to tire of their beauty. Kalimpong was populated by three main tribes – the Lepchas, the Bhutias and the Nepalese. John was attracted to working with the Lepchas, the original inhabitants.The foundation of the Kalimpong Mission was a result of the visit of the Reverends, Dr. McLeod and Dr. Watson to the area. The Mission compound consisted of sixteen acres of land close to the Kalimpong bazaar and housed the Guild Mission as well as a training school for catechists. John and Katherine decided to work with the mission. Over the years there was a growing incidence of disease and it became obvious that a small hospital was essential. A hospital with 25 beds was opened in 1893 in the name of John’s mentor, Prof. Charteris, where compounders were trained and much later in 1912, nurses too. Apart from the hospital, John felt the need for a Church, which was later approved and built. |

|

|

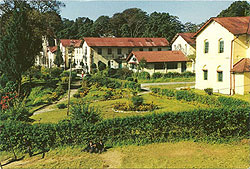

John soon became interested in the Anglo-Indian problem and showed a special interest in this community. On his return to Kalimpong in 1898, he increasingly took up activities for the welfare of the Anglo-Indian community to which he was to devote a greater part of the rest of his life. Also known as Eurasians, the term Anglo-Indians referred to those of mixed origin. In the earlier days of the East India Company, Britishers of all ranks formed liaisons with local women. The children born as a result were not always born out of marriage but were generally looked after by their British fathers. The gradual arrival of British women caused these liaisons, which had been open and above board, to go underground. Arrangements became the subject of malicious gossip and the Anglo-Indian community found itself ostracised. John had come across a great number of Anglo-Indian children on his frequent visits to the tea plantations of Darjeeling, the Dooars and Terai, and his heart was touched by their plight. He felt their sufferings were unjust and something needed to be done for them. In May 1900, John decided to set up the Homes in Kalimpong, for children who had never known a father’s love and had no identification with their country of birth. In August that year, John acquired 100 acres of land above the Mission on the slopes of the Deolo Hill where he would house his intended beneficiaries. It was at this juncture of John’s life that he became determined that he would, through his vision and fierce resolve, leave a legacy – Dr. Graham’s Homes. John soon became interested in the Anglo-Indian problem and showed a special interest in this community. On his return to Kalimpong in 1898, he increasingly took up activities for the welfare of the Anglo-Indian community to which he was to devote a greater part of the rest of his life. Also known as Eurasians, the term Anglo-Indians referred to those of mixed origin. In the earlier days of the East India Company, Britishers of all ranks formed liaisons with local women. The children born as a result were not always born out of marriage but were generally looked after by their British fathers. The gradual arrival of British women caused these liaisons, which had been open and above board, to go underground. Arrangements became the subject of malicious gossip and the Anglo-Indian community found itself ostracised. John had come across a great number of Anglo-Indian children on his frequent visits to the tea plantations of Darjeeling, the Dooars and Terai, and his heart was touched by their plight. He felt their sufferings were unjust and something needed to be done for them. In May 1900, John decided to set up the Homes in Kalimpong, for children who had never known a father’s love and had no identification with their country of birth. In August that year, John acquired 100 acres of land above the Mission on the slopes of the Deolo Hill where he would house his intended beneficiaries. It was at this juncture of John’s life that he became determined that he would, through his vision and fierce resolve, leave a legacy – Dr. Graham’s Homes. |

|

|

In 1908, Dr. Graham succeeded in convincing James Purdie, a welfare worker in a Glasgow prison, to join him in his work in Kalimpong. James Purdie soon became Dr. Graham’s right hand man and an important member of his team. He was a good accountant and nursed the Homes’ finances efficiently, investing well and building up the necessary reserves to ensure a constant flow of funds.

Together, Dr. Graham and James Purdie were a great team. The two did not compete for the boys’ affection and attention. The older boys tended to take to James Purdie who would often take them trekking to Sikkim. Although the children were thoroughly protected and nurtured in the safety of the Homes, Dr. Graham and James Purdie were careful not to paint an idyllic picture of life in the outside world. Life in Calcutta was challenging for all those who left Kalimpong in search of jobs and the duo ensured that the children were well aware of this fact, often having to manage the fear and anxiety of those leaving the Homes. For these children, the construction of the Birkmyre Hostel in Calcutta was a great help. The Hostel was a generous gift to Dr. Graham from Sir Archibald Birkmyre for the boys of Kalimpong.Dr. Graham’s influence in Kalimpong in its formative years was profound and touched the lives of all sections of the community. It is significant that it is not only in missionary circles that he is called Graham of Kalimpong – the two names cannot be separated. Without fifty-two years of Dr. Graham’s presence, Kalimpong would still have grown, but perhaps not in such an orderly way. It would still, without Dr. Graham, have had its beautiful setting, but the spirit of the place would have been vastly different. There is today a tolerance in Kalimpong. A width of vision among its responsible citizens that transcends community prejudice, religious differences and caste inequalities. In 1908, Dr. Graham succeeded in convincing James Purdie, a welfare worker in a Glasgow prison, to join him in his work in Kalimpong. James Purdie soon became Dr. Graham’s right hand man and an important member of his team. He was a good accountant and nursed the Homes’ finances efficiently, investing well and building up the necessary reserves to ensure a constant flow of funds.

Together, Dr. Graham and James Purdie were a great team. The two did not compete for the boys’ affection and attention. The older boys tended to take to James Purdie who would often take them trekking to Sikkim. Although the children were thoroughly protected and nurtured in the safety of the Homes, Dr. Graham and James Purdie were careful not to paint an idyllic picture of life in the outside world. Life in Calcutta was challenging for all those who left Kalimpong in search of jobs and the duo ensured that the children were well aware of this fact, often having to manage the fear and anxiety of those leaving the Homes. For these children, the construction of the Birkmyre Hostel in Calcutta was a great help. The Hostel was a generous gift to Dr. Graham from Sir Archibald Birkmyre for the boys of Kalimpong.Dr. Graham’s influence in Kalimpong in its formative years was profound and touched the lives of all sections of the community. It is significant that it is not only in missionary circles that he is called Graham of Kalimpong – the two names cannot be separated. Without fifty-two years of Dr. Graham’s presence, Kalimpong would still have grown, but perhaps not in such an orderly way. It would still, without Dr. Graham, have had its beautiful setting, but the spirit of the place would have been vastly different. There is today a tolerance in Kalimpong. A width of vision among its responsible citizens that transcends community prejudice, religious differences and caste inequalities. |

|

|

||

In 1903, Dr. Graham received his first public award, the Kaiser-i-Hind Medal, awarded to him by the Government. In 1904, the University of Edinburgh conferred on him the Degree of Doctor of Divinity. So successful and unique was Dr. Graham’s work and mission that it began to spread to South India when he was asked to travel to Madras to speak about his work in Kalimpong to a group of influential people, amongst whom was Sir Arthur Lawley, the Governor of Madras. It was this meeting in 1911 that provided the inspiration for the establishment of St. George’s Homes in Kodaikanal which had the same purpose as did the Kalimpong Homes. In 1903, Dr. Graham received his first public award, the Kaiser-i-Hind Medal, awarded to him by the Government. In 1904, the University of Edinburgh conferred on him the Degree of Doctor of Divinity. So successful and unique was Dr. Graham’s work and mission that it began to spread to South India when he was asked to travel to Madras to speak about his work in Kalimpong to a group of influential people, amongst whom was Sir Arthur Lawley, the Governor of Madras. It was this meeting in 1911 that provided the inspiration for the establishment of St. George’s Homes in Kodaikanal which had the same purpose as did the Kalimpong Homes.

|

|

|

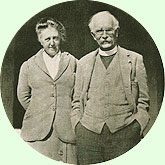

Mrs. Graham was always deeply concerned about the Lepcha and Nepalese womenfolk. Life was hard for them – early marriage, child bearing at regular intervals, and little or no money for any kind of extras. She felt that if they could be engaged in the making of some useful and productive crafts, they might be able to supplement their household incomes. She decided that cottage industries would be the answer.As traditional Tibetan weaves and designs were much in demand amongst the army and planters, weaving as a cottage industry was a natural choice. With contributions from friends, Mrs. Graham started a weaving school for the women as well as a lace school. She also encouraged them to take up poultry rearing and turkey breeding. For the men, craft instruction was started and they were trained and encouraged to take up carpentry, woodcarving and silver work.

Dr. Graham felt that the development of cottage industries would benefit not only the Himalayan area but all of India and both he and Mrs. Graham were pioneers in the field. He saw Kalimpong as a training school for teachers of crafts in the district and saw Sikkim as a possible area for expansion. For her work in developing cottage industries, Mrs. Graham was awarded the Kaiser-i-Hind Medal in 1916.

The industries grew and flourished and eventually came to be known as Arts and Crafts. Bunty and Norman Odling, Dr. Graham’s daughter and son-in-law, were in charge of this area of work from 1924 to just prior to Independence and made an invaluable contribution to its expansion which helped in the economic and social empowerment of the local community. Mrs. Graham was always deeply concerned about the Lepcha and Nepalese womenfolk. Life was hard for them – early marriage, child bearing at regular intervals, and little or no money for any kind of extras. She felt that if they could be engaged in the making of some useful and productive crafts, they might be able to supplement their household incomes. She decided that cottage industries would be the answer.As traditional Tibetan weaves and designs were much in demand amongst the army and planters, weaving as a cottage industry was a natural choice. With contributions from friends, Mrs. Graham started a weaving school for the women as well as a lace school. She also encouraged them to take up poultry rearing and turkey breeding. For the men, craft instruction was started and they were trained and encouraged to take up carpentry, woodcarving and silver work.

Dr. Graham felt that the development of cottage industries would benefit not only the Himalayan area but all of India and both he and Mrs. Graham were pioneers in the field. He saw Kalimpong as a training school for teachers of crafts in the district and saw Sikkim as a possible area for expansion. For her work in developing cottage industries, Mrs. Graham was awarded the Kaiser-i-Hind Medal in 1916.

The industries grew and flourished and eventually came to be known as Arts and Crafts. Bunty and Norman Odling, Dr. Graham’s daughter and son-in-law, were in charge of this area of work from 1924 to just prior to Independence and made an invaluable contribution to its expansion which helped in the economic and social empowerment of the local community.

|

|

|

The rapid expansion of the Homes became a matter of concern to the Foreign Missions Committees as budgets were constrained. This became an impediment to Dr. Graham;s work, one of several challenges that he had to face. He also endured hardship and even resentment, such as resistance from the Nepali Christians, who felt that his focus had shifted from them to the Anglo-Indian community. Dr. Graham and other missionaries were also subject to criticism from them and the Lepcha Christian communities who felt that they had only been educated for vocational pursuits and not for business, trade or commerce.Dr. Graham was a great believer in the Cottage System. He believed that such a system, with the presence of House Parents in each Cottage, lent a unique dimension to the Homes – providing the children with a “home” and teaching them to be responsible, interdependent, caring and collaborative in their behaviour.He personally supervised the building of the Cottages. All of them were carefully sited and to withstand the annual torrential monsoon downpours and the attendant possibility of landslides. The plans of Quarrier’s Bridge of Weir Cottages were adapted to suit monsoon conditions. Dr. Graham not only supervised the purchase of timber, accompanying the Forest Officer to select trees for cutting, but was equally careful in selecting workmen.

The Cottage System made the Homes a unique place in India. Dr Graham’s aim was the same as Quarrier’s – to compensate the child and to prepare him to face life with confidence, a confidence which had to be carefully built by love and concern.

Despite the fact that the Grahams’ own children were separated from their parents for long durations, they were never made to feel left out or neglected. They were always told that they came first in their parent’s affection, although their parents had a lot of love to spare for other children. During their long absence from home, the Grahams’ would write letters each week to their children and send them pocket money as well.

During the First World War, expansion of the work at the Homes slowed down as food prices escalated and staff left to make up for wartime duties. Over 150 Dr. Graham’s Homes’ Boys who had passed out between 1904 and 1914 fought at all fronts across the world. This did Dr. Graham proud and he was able to demonstrate to skeptics in Australia and New Zealand that the Anglo-Indian community was as tough, reliable and patriotic as any other.

Dr. Graham felt that there was need for a holiday home where ex-students returning to Kalimpong could meet friends and recall their days at the Homes. This became a reality with the James Purdie Holiday Home which was built in 1939. Another holiday home, the ‘Ahava’ was constructed for missionaries and friends. The rapid expansion of the Homes became a matter of concern to the Foreign Missions Committees as budgets were constrained. This became an impediment to Dr. Graham;s work, one of several challenges that he had to face. He also endured hardship and even resentment, such as resistance from the Nepali Christians, who felt that his focus had shifted from them to the Anglo-Indian community. Dr. Graham and other missionaries were also subject to criticism from them and the Lepcha Christian communities who felt that they had only been educated for vocational pursuits and not for business, trade or commerce.Dr. Graham was a great believer in the Cottage System. He believed that such a system, with the presence of House Parents in each Cottage, lent a unique dimension to the Homes – providing the children with a “home” and teaching them to be responsible, interdependent, caring and collaborative in their behaviour.He personally supervised the building of the Cottages. All of them were carefully sited and to withstand the annual torrential monsoon downpours and the attendant possibility of landslides. The plans of Quarrier’s Bridge of Weir Cottages were adapted to suit monsoon conditions. Dr. Graham not only supervised the purchase of timber, accompanying the Forest Officer to select trees for cutting, but was equally careful in selecting workmen.

The Cottage System made the Homes a unique place in India. Dr Graham’s aim was the same as Quarrier’s – to compensate the child and to prepare him to face life with confidence, a confidence which had to be carefully built by love and concern.

Despite the fact that the Grahams’ own children were separated from their parents for long durations, they were never made to feel left out or neglected. They were always told that they came first in their parent’s affection, although their parents had a lot of love to spare for other children. During their long absence from home, the Grahams’ would write letters each week to their children and send them pocket money as well.

During the First World War, expansion of the work at the Homes slowed down as food prices escalated and staff left to make up for wartime duties. Over 150 Dr. Graham’s Homes’ Boys who had passed out between 1904 and 1914 fought at all fronts across the world. This did Dr. Graham proud and he was able to demonstrate to skeptics in Australia and New Zealand that the Anglo-Indian community was as tough, reliable and patriotic as any other.

Dr. Graham felt that there was need for a holiday home where ex-students returning to Kalimpong could meet friends and recall their days at the Homes. This became a reality with the James Purdie Holiday Home which was built in 1939. Another holiday home, the ‘Ahava’ was constructed for missionaries and friends.

|

| |||

|

|

Perhaps the greatest honour bestowed on Dr. Graham was when he was called to the Moderator’s Chair of the General Assembly of the Church of Scotland. He was the first missionary of the Church of Scotland to be called to this high office.It was appropriate that this honour should come to Dr. Graham in 1931, the year he retired from the Kalimpong Mission, after forty-two years of service. Retirement however, did not involve leaving his beloved Kalimpong, for he was to move up to the St. Andrews Colonial Homes, to continue his work. Dr. Graham accepted the Moderatorship of the General Assembly with a degree of trepidation as he was deeply aware of the tremendous honour that had been conferred on him and he felt he should accept it on behalf of all missionaries, many of whom laboured in difficult surroundings without much public recognition of their service and endeavours. He therefore regarded his appointment as recognition by the Church of the importance of Foreign Missions.

Although Dr. Graham was excused his full term as Moderator so that he could return to India, like most Moderators, he had visited as many cities, towns and villages as he could during his term. Before setting out for India, he preached at Liverpool Cathedral at the invitation of Bishop Albert. In 1932, it was unusual for a Presbyterian to be asked to preach in an Anglican Church and Dr. Graham’s sermon gained wide coverage in the English newspapers.

He returned to Kalimpong on 18th March 1932. He had been honoured by his Church and met the greatest in the land. None who had met him would forget the humility of the man, his twinkling blue eyes and his warm handshake. Now that he had left the honours, the crowds and troubled Europe and returned to the peace of the mountains, all Kalimpong welcomed him back, proud that he had won such distinction in his own country. Christians, Hindus, Buddhists and Muslims turned out to honour him on his return. They had given him on loan for a year and people of all communities were happy that Kalimpong’s most famous son was back. Perhaps the greatest honour bestowed on Dr. Graham was when he was called to the Moderator’s Chair of the General Assembly of the Church of Scotland. He was the first missionary of the Church of Scotland to be called to this high office.It was appropriate that this honour should come to Dr. Graham in 1931, the year he retired from the Kalimpong Mission, after forty-two years of service. Retirement however, did not involve leaving his beloved Kalimpong, for he was to move up to the St. Andrews Colonial Homes, to continue his work. Dr. Graham accepted the Moderatorship of the General Assembly with a degree of trepidation as he was deeply aware of the tremendous honour that had been conferred on him and he felt he should accept it on behalf of all missionaries, many of whom laboured in difficult surroundings without much public recognition of their service and endeavours. He therefore regarded his appointment as recognition by the Church of the importance of Foreign Missions.

Although Dr. Graham was excused his full term as Moderator so that he could return to India, like most Moderators, he had visited as many cities, towns and villages as he could during his term. Before setting out for India, he preached at Liverpool Cathedral at the invitation of Bishop Albert. In 1932, it was unusual for a Presbyterian to be asked to preach in an Anglican Church and Dr. Graham’s sermon gained wide coverage in the English newspapers.

He returned to Kalimpong on 18th March 1932. He had been honoured by his Church and met the greatest in the land. None who had met him would forget the humility of the man, his twinkling blue eyes and his warm handshake. Now that he had left the honours, the crowds and troubled Europe and returned to the peace of the mountains, all Kalimpong welcomed him back, proud that he had won such distinction in his own country. Christians, Hindus, Buddhists and Muslims turned out to honour him on his return. They had given him on loan for a year and people of all communities were happy that Kalimpong’s most famous son was back. |

| |

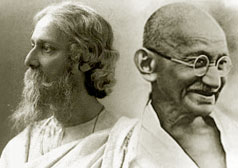

Dr. Graham was keenly interested in the political movement that was growing in intensity towards the end of his life. Kalimpong, of course, was far away from the political scene but he was conscious of the serious nature of the demands for Independence. He had nothing but admiration for Mahatma Gandhi and always referred to him in his notes with the greatest respect. Gandhi’s philosophy of life was much in tune with Dr. Graham’s own beliefs. He knew that Indians felt capable of ruling and looking after their own destiny and he was remarkably realistic in his views. Dr. Graham was keenly interested in the political movement that was growing in intensity towards the end of his life. Kalimpong, of course, was far away from the political scene but he was conscious of the serious nature of the demands for Independence. He had nothing but admiration for Mahatma Gandhi and always referred to him in his notes with the greatest respect. Gandhi’s philosophy of life was much in tune with Dr. Graham’s own beliefs. He knew that Indians felt capable of ruling and looking after their own destiny and he was remarkably realistic in his views.It would be true to say, however, that he feared for India and viewed the threat of India’s withdrawal from the Empire with the gravest misgivings. By suggesting that India and Britain should be co-partners in a greater Empire, Dr. Graham probably meant that some degree of political freedom be given to India within the framework of the Empire. It is doubtful whether he was looking forward to India having independent status within the Commonwealth. Dr. Graham had also developed a close relationship with Rabindranath Tagore, whose son had a home in Kalimpong and who was a frequent visitor to the town. The two old gentlemen had long discussions about politics and philosophy and had a healthy respect for each other’s views. Dr. Graham had become accquainted with Rabindranath Tagore in 1938 when Tagore came to Kalimpong to recuperate after a serious illness. When Dr. Graham was ill in the same year, Tagore called on him. In 1941, Rabindranath Tagore passed away and Dr. Graham paid a glowing tribute to him not only as a poet but as a musician, preacher, politician and educationist. |

|

|

On 15th May 1944 the Homes would become Reverend Dr. John Anderson Graham’s final resting place and he would be fondly remembered as ‘Daddy Graham’ for decades to come.Reverend Dr. John Anderson Graham’s was a full life, a satisfying and creative life, and he has left behind him, in much of the Mission work and Dr. Graham’s Homes, fitting memorials. Despite political pressures, both these institutions continue to render service to India. So surely and soundly were the foundations of both institutions laid, that the winds of change have not altered the basic aims and designs of either the Mission or the Homes.

Professor Charteris spoke of Reverend Dr. John Anderson Graham as a person who had the “brain of a statesman, the heart of a little child and the record of a hero.” While he exemplified these three attributes, statesmanship, innocence and courage, perhaps his great faith in God should be added to these. He never had any doubt that God would favour and bless his work. Throughout his life he believed, too, in humanity and man’s inherent goodness. Added to these qualities were his almost super-human work habits. He drove himself hard, and every hour of the day was filled. He found absorption and interest in all that he did, and whether he was in Kalimpong, Calcutta, on furlough or on one of his overseas tours, his capacity for hard work, both physical and mental, was astonishing.

He saw the peaks. Not only the glory of the Kanchenjunga and the other towering Himalayan peaks, but something of the glory of God, the peaks of endeavour which can be reached with God’s help. Reverend Dr. John Anderson Graham accepted the call of God to high adventure and endeavour in an isolated part of His Kingdom. That corner flourished, thanks to the qualities of God’s chosen servant, and Reverend Dr. John Anderson Graham made a garden out of a wilderness.

In the Katherine Graham Memorial Chapel is one of the simplest and yet most effective epitaphs. It reads:

“Dr. Graham who loved children founded these Homes in 1900.”

Love was his greatest virtue, and he had it in abundance. On 15th May 1944 the Homes would become Reverend Dr. John Anderson Graham’s final resting place and he would be fondly remembered as ‘Daddy Graham’ for decades to come.Reverend Dr. John Anderson Graham’s was a full life, a satisfying and creative life, and he has left behind him, in much of the Mission work and Dr. Graham’s Homes, fitting memorials. Despite political pressures, both these institutions continue to render service to India. So surely and soundly were the foundations of both institutions laid, that the winds of change have not altered the basic aims and designs of either the Mission or the Homes.

Professor Charteris spoke of Reverend Dr. John Anderson Graham as a person who had the “brain of a statesman, the heart of a little child and the record of a hero.” While he exemplified these three attributes, statesmanship, innocence and courage, perhaps his great faith in God should be added to these. He never had any doubt that God would favour and bless his work. Throughout his life he believed, too, in humanity and man’s inherent goodness. Added to these qualities were his almost super-human work habits. He drove himself hard, and every hour of the day was filled. He found absorption and interest in all that he did, and whether he was in Kalimpong, Calcutta, on furlough or on one of his overseas tours, his capacity for hard work, both physical and mental, was astonishing.

He saw the peaks. Not only the glory of the Kanchenjunga and the other towering Himalayan peaks, but something of the glory of God, the peaks of endeavour which can be reached with God’s help. Reverend Dr. John Anderson Graham accepted the call of God to high adventure and endeavour in an isolated part of His Kingdom. That corner flourished, thanks to the qualities of God’s chosen servant, and Reverend Dr. John Anderson Graham made a garden out of a wilderness.

In the Katherine Graham Memorial Chapel is one of the simplest and yet most effective epitaphs. It reads:

“Dr. Graham who loved children founded these Homes in 1900.”

Love was his greatest virtue, and he had it in abundance. |

At the age of sixteen, John became a clerk to the General Board of Lunacy, Edinburgh. It was during this period that he became actively engaged in Church affairs as a member of St. Bernard’s Parish Church and also became the Secretary of the Young Men’s Fellowship Association. Soon John grew disenchanted with the dull grind of office routine. Encouraged by Rev. John McMurtrie, the then minister of St. Bernard’s Parish Church, John resigned from government service to prepare for the Ministry and studied at Edinburgh University for a Masters degree, which he completed in 1885. It was a great step for him to take because his education until then had been sketchy and interrupted. However, his motivation lay in preparing himself for his ‘true vocation’. During the six years he was at Edinburgh University, John also worked as a clerk to The Christian Life and Work Committee. It was here that he learnt the power of propaganda and dissemination of information. In 1886, he went to Dresden in Germany for a brief period of study. In August that year, he went through a deeply religious experience that had a profound impact on him. It was from here that he wrote to his Professor offering himself for service as a missionary.

At the age of sixteen, John became a clerk to the General Board of Lunacy, Edinburgh. It was during this period that he became actively engaged in Church affairs as a member of St. Bernard’s Parish Church and also became the Secretary of the Young Men’s Fellowship Association. Soon John grew disenchanted with the dull grind of office routine. Encouraged by Rev. John McMurtrie, the then minister of St. Bernard’s Parish Church, John resigned from government service to prepare for the Ministry and studied at Edinburgh University for a Masters degree, which he completed in 1885. It was a great step for him to take because his education until then had been sketchy and interrupted. However, his motivation lay in preparing himself for his ‘true vocation’. During the six years he was at Edinburgh University, John also worked as a clerk to The Christian Life and Work Committee. It was here that he learnt the power of propaganda and dissemination of information. In 1886, he went to Dresden in Germany for a brief period of study. In August that year, he went through a deeply religious experience that had a profound impact on him. It was from here that he wrote to his Professor offering himself for service as a missionary. Mrs. Graham passed away on 15th May 1919. The imposing Katherine Graham Chapel, the fulcrum around which the work at the Homes revolves, was built by Reverend Dr. John Anderson Graham as a tribute to his beloved wife. Their life together was one of love and compassion, of commitment to children and to all those living in and around Kalimpong. Katherine Graham’s passing away left a deep void in Dr. Graham’s life, but he soldiered on, in full knowledge that her spirit would always be beside him, encouraging him to continue the work they had both dedicated their lives to.

Mrs. Graham passed away on 15th May 1919. The imposing Katherine Graham Chapel, the fulcrum around which the work at the Homes revolves, was built by Reverend Dr. John Anderson Graham as a tribute to his beloved wife. Their life together was one of love and compassion, of commitment to children and to all those living in and around Kalimpong. Katherine Graham’s passing away left a deep void in Dr. Graham’s life, but he soldiered on, in full knowledge that her spirit would always be beside him, encouraging him to continue the work they had both dedicated their lives to.